What the Lawn Remembers

Reclaiming lawn as a space for joy, not control.

A Field Journal Audioessay edited by Tom T. Young

Listen Along Below (~12 min)

I. The Lawn as Invitation

Lawn We Love: the Interstitial Canvas

I sit three stories up, looking down onto a courtyard of grass, walled in by apartment facades, accompanied by a few arborvitae, shrubs in mulch, and young shade trees struggling to find their shape. I’ve lived here about a year now, and across the seasons I’ve seen this big lawn host life: dogs chasing after their owners, kids playing hopscotch along its concrete frame, a dad teaching his son how to play tee-ball.

But earlier this spring, something exciting happened. Something big.

I watched from my balcony as a gaggle of kids, in every pastel shade imaginable, exploded across the lawn in search of Easter eggs. They sprinted, stumbled, baskets spilling with plastic eggs behind them. It was loud, chaotic, perfect. It was the kind of moment third spaces are meant to hold—where joy ruptures out of the ordinary.

This is what lawn can do when it’s at its best.

It isn’t about visual perfection. It isn’t about status or control. It’s about the space it creates for us to gather, to play, to move, to be. Lawn is what allows a community to emerge into public life. It’s where we roll, dance, wrestle, stretch, walk barefoot, play football, paint, picnic, sled in winter, or simply lie on our backs and look up at the sky.

When I produced theater outdoors, we would perform in public gardens and historic spaces (shout out to the Rutgers Gardens!). The landscape itself became the set, the context. People arrived with folding chairs and picnic blankets. They wandered among lilacs and dogwoods, then sat on the grass to watch Robin Hood emerge from the shrubs.

Grass isn’t the only walkable surface—there’s gravel, mulch, wood, concrete—but there’s something soft and sensorial about grass. Something human. It invites bodies to touch down. It asks for interaction. And when done right, it becomes a kind of democratic material: not ornamental, but participatory.

But lawn isn’t neutral. It’s often overlooked, taken for granted. Most people don’t think about it until it’s patchy, weedy, or flooded. We’ve been conditioned not to notice it. That’s part of its power, and part of its danger. When something becomes so common that we stop seeing it, we stop questioning it… Then we stop choosing it.

So what if we treated it as a choice?

What if we stopped defaulting to lawn and started designing for connection? What if lawn was framed by life: by gardens that feed pollinators, trees that shelter us, and beds of plants that nourish the soil? What if lawn wasn’t the whole story, but a part of something more alive?

Because lawn isn’t the problem. But when it becomes the backdrop to everything—when it replaces the wild, the layered, the complex—we lose more than we realize.

And maybe that’s the question worth asking:

If we’ve been trained to want lawn everywhere,

what exactly have we been trained to forget?

II. The Lawn We Inherited

The grass is greener where the gasoline flows.

Somewhere along a highway, you’ve seen it: a guy on a riding mower, trimming a narrow, steep slope next to an off-ramp. Just grass. Just there. Just because.

And once you see it (really see it) you can’t unsee it. It’s in medians. Outside every bank, strip mall, and post office. It’s stitched between buildings, wrapped around sidewalks, rolled out in front of schools, libraries, hospitals. It’s the default skin of American space.

And suddenly, the number—40 to 50 million acres of it in the U.S. alone—makes grim sense.

We’ve covered the country in something we barely think about. And the cost of keeping it alive? Staggering.

Lawns are the largest irrigated crop in the U.S., more than corn, wheat, and fruit combined.

– NASA, 2005In many cities, 30–60% of household water use goes to landscape irrigation alone.

– EPAGas-powered lawn equipment emits 11x more pollution per hour than a modern car.

– CARB, CaliforniaOver 90 million pounds of fertilizers and pesticides are dumped on lawns annually.

– U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service

That’s not a yard. That’s an industry.

A performance of control, costumed in green.

(see references & citations to facts below)

Central Park, and the Trouble with Beautiful Things

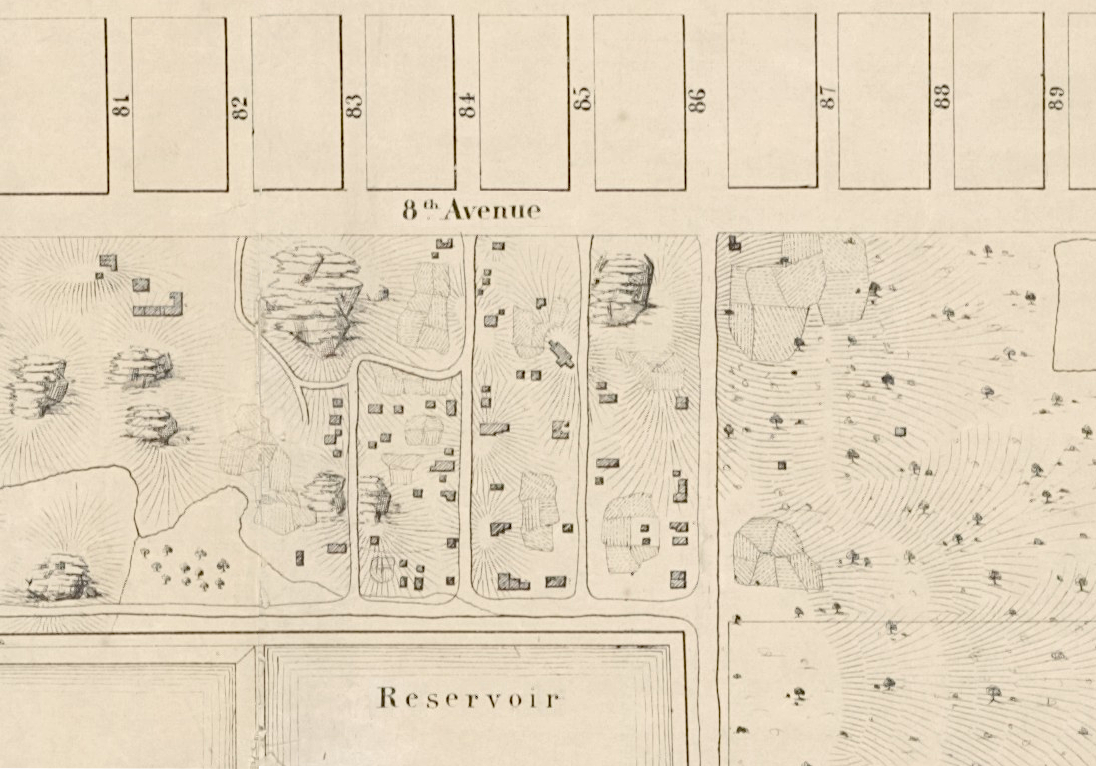

Even our most beloved green spaces have complicated roots. Central Park—iconic, ecological, universally adored—is also a site of erasure. Before it was a park and became New York City’s big lawn, it was home to Seneca Village, a thriving community of Black and Irish landowners who were forcibly displaced in the 1850s.

Today, the park stands as proof that lawn can be a powerful third space full of life, joy, and gathering. But it also reminds us that how land is shaped, and who it's shaped for, carries consequences.

Lawn, like the park itself, is not inherently good or bad. It’s a medium. A design decision. A cultural story. And if we’ve inherited it unquestioned, then it’s worth asking: what story have we been told?

The tyranny of custom

What’s wild is that most people don’t choose lawn consciously. You inherit it. You buy a house, and there it is: the obligatory green rectangle, front and back. A visual symbol of responsibility and respectability, passed from suburb to suburb.

But lawn isn’t natural.

It’s not inevitable.

It’s historical.

Before it was replaced with lawns and parking lots, this land was shaped by Indigenous stewardship—landscapes managed with intention, reciprocity, and deep ecological knowledge. Meadows, prairies, and woodlands weren’t wilderness to be tamed; they were cultural landscapes, full of meaning, care, and use.

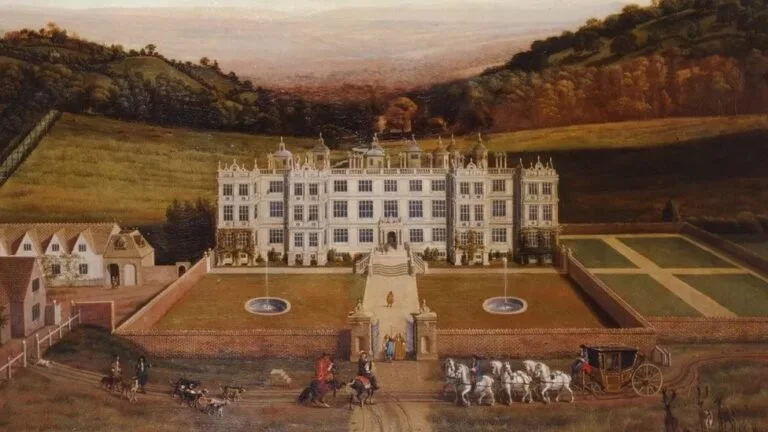

Trimmed grass as aesthetic began in the gardens of 17th-century English and French aristocrats, where open lawns signified wealth: land you didn’t need to farm, land you could simply show off. When white settlers brought this aesthetic to North America, it merged with the ideas of ownership, order, and productivity. By the post-WWII housing boom, it became an American norm: green lawn, white fence, good citizen.

HOAs wrote it into bylaws. Cities coded it into compliance. And today, we still see anything that breaks that visual code as “messy,” “unkempt,” or even “unsafe.”

But look closer.

When you treat soil like a stage for visual perfection—stripped bare, compacted, chemically stabilized—you destroy the very thing it’s supposed to support. Lawns, in much of the country, function more like impervious surface than living system. They shed water instead of absorbing it. They can contribute to runoff and erosion when mismanaged. They leach chemicals. They heat the air.

And when they brown or flood or falter, we blame the weather. Or the weeds. Or the soil.

Anything but the design itself.

The earth emerges from beneath the concrete,

not the other way around.

The Lawn Industrial Complex

If this all sounds like a hustle… it kind of is.

The U.S. landscaping industry is worth over $129 billion, driven by the constant churn of mowing, spraying, watering, reseeding, and replacing. Think of it like a subscription model: beauty with a price tag and a maintenance contract.

We’ve been trained to associate lawn care with morality. A tidy yard is a good neighbor. A little mess? A violation. You’re not just cutting grass, you’re upholding an aesthetic system that profits from your compliance. This system thrives on:

Chemical companies selling fixes to problems lawn shouldn’t have.

HOAs and zoning laws enforcing conformity.

Contractors and irrigation companies banking on the idea that nature needs intervention.

And it doesn’t impact everyone equally.

Low-income and BIPOC communities bear the brunt: both as underpaid landscapers, often exposed to toxic chemicals, and as residents in under-shaded, heat-vulnerable neighborhoods with limited access to restorative green space.

Even your feelings have been conditioned. If a dandelion in your lawn looks wrong instead of right… that’s monoculture doing its job.

This isn’t just lawn. It’s a compliance landscape.

III. The Lawn We Should Choose

Care is a design principle.

So what do you do with your lawn?

First of all, thank you for asking. That’s a great start.

Maybe you have a dog. Maybe your grandkids play soccer. Maybe you host movies under the stars. Beautiful. Let’s keep the parts of the lawn that serve that joy. Let’s preserve the lawn you actually use.

But let’s also start listening to the land.

Let’s observe where the sun hits, where the water pools, what the soil is asking for. Let’s find the quiet corners where lawn isn’t needed, and ask what could live there instead.

Maybe it’s a patch of native perennials. Maybe it’s a tree that casts shade.

Maybe it’s a garden that feeds the bees, the soil, your belly, and your spirit.

Let’s turn your patch of green into a patchwork of beauty. A place where play still happens, but where wildflowers bloom beside it. Where plants support pollinators and people at once. Where the landscape regenerates itself, like a conversation that keeps growing, season after season, year after year, generation after generation.

Because what we’re doing here isn’t just lawn removal. It’s relationship repair.

This is what the land remembers

What I wish we saw more of:

Spaces to gather.

Spaces to speak.

Spaces to protest.

Spaces to make art.

Spaces to trade food.

Spaces where kids run through trees.

Spaces that reflect who we are and where we are,

not just who we were told to be.

And they should be everywhere. No one should have to drive across town to feel like they belong on the land. Whether you’re walking, rolling, strolling, or sprinting, these places should welcome you. They should pull you in.

That’s what universal design really means.

That’s what care looks like, shaped into soil.

We need landscapes designed not just for function or beauty, but for belonging.

The radical vision is simple

I believe lawn will become precious again.

Not because we’ll lose it entirely, but because we’ll start treating it with the intention it deserves.

We’ll keep small patches of it—for playing catch, for rolling around, for picnics under the open sky—because those uses will be worth the space they take.

And everything around them? That’s where life will return.

Wildflower meadows. Edible gardens. Cultural plantings.

Native species reappearing. Soil rebuilding. Birds nesting.

Children learning not from worksheets,

but from walking through a living system.

This work doesn’t just change yards.

It changes minds.

It changes HOAs.

It changes city ordinances.

It changes who gets to design, who gets to belong, and what we call beautiful.

A new kind of spring

Imagine this:

the same Easter egg hunt.

But this time, the kids are searching beneath blooming red columbine and low-hanging serviceberry branches. They peek behind old logs, along the edge of a stream, among cattail marshes. Some eggs are nestled under tiarella blooms. Others sit among the leaves of Jacob’s ladder, their colors echoing the children’s own spring dresses.

Off in the clearing, teenagers toss a football as the light turns golden.

The littlest kids sprawl on picnic blankets, laughing over their candy.

The lawn is still there, gently held in the center of it all.

While everything around it hums…

Opportunity is in every landscape.

From the ground up, Design Ecosystems with us.

References & Resources

Lawns as the Largest Irrigated Crop in the U.S.

A 2005 NASA-led study estimated that turf grass covers about 63,000 square miles in the U.S., making it the largest irrigated crop—surpassing corn, wheat, and fruit orchards combined. Source

Household Water Use for Landscape Irrigation

According to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), landscape irrigation accounts for nearly one-third of all residential water use, totaling nearly 9 billion gallons per day. Source

Emissions from Gas-Powered Lawn Equipment

The California Air Resources Board (CARB) states that operating a commercial lawn mower for one hour emits as much smog-forming pollution as driving a new light-duty passenger car about 300 miles. Source

Fertilizer and Pesticide Use on Lawns

Americans apply approximately 90 million pounds of fertilizers and pesticides to their lawns annually, contributing to environmental concerns such as water pollution and harm to wildlife. Source

Currently Reading

Braiding Sweetgrass by Robin Wall Kimmerer

Indigenous Wisdom Scientific

Knowledge and the Teachings of Plants

On Deck

Land Power by Michael Albertus

Who Has It, Who Doesn't, and

How That Determines the Fate of Societies